Eel Soup

Essay

Selen Ansen’s ten-day poetic and theoretical exploration of Jan Van Imschoot’s works exhibited at the S.M.A.K. An essay about ghosts, Aby Warburg, Georges Bataille and Edouard Manet, among others.

The women say that they expose their genitals so that the sun may be reflected therein as in a mirror.

Monique Wittig, The Guérillères [1]

At that moment, I understood that we were going to go downwards. It was over, we would never go up.

Georges Bataille, Éponine [2]

One day, the iconologist Aby Warburg, who studied the ‘survival’ and ‘revenance’ of the gestures of pathos through the ages, believed himself to be Saturn [3]. Suffering from episodes of delirium at the end of the First World War, he was persuaded that the meat he ingested was the flesh of his children. This personal chaos gave him further proof that bygones resurface in the present – and that the past produces the future. In the short time between his recovery and death, Warburg continued his study of the migration of forms by means of his Mnemosyne Atlas (1924–9). His montage of heterogeneous images invalidates the chronological conception of historical time through the use of anachronisms and strives to reveal that the visual culture of humanity is made up of ‘ghosts’: expressive forms from the past that return to the surface to haunt the images produced by the living. In this compilation of images, one sees the capacity of gestures to never quite die – and to resurface at any moment.

DAY 1 / […]

As for me, I look at Jan’s works and see something entirely different. In them I see existences magnetised by the ground, warning me that everything falls and keeps falling. I see the putrescible flesh and prosaic bodies assuring us that we will not fly / that we die and reach climax here on earth. I also see lines of forces and oppositions; the rise of impulses and fantasies; the descent of solids and fluids, the fall of ideals; means of inebriation alongside instruments of crime; the macabre rubbing shoulders with laughter.

DAY 2 / […]

Everything falls and keeps falling. The fall of things on high counterbalanced by the rise of things down low suggests to me that Jan’s figurative approach is complicit in a form of abstraction; that his gesture does not aim to depict violence for its own sake, nor even to feed its desire for overkill; that it seeks instead to highlight the repression of violence. To show that buried things resurface, loaded with the weight of their accumulated silence, with the strength to impact the present and impress the future. Jan has (at least) one brother-in-arms in his fight against the levelling out of images, the civilising fable that makes violence the great other of humankind, the division between humanitas and animalitas which is a cultural decision and not a state of affairs. In the last century, ‘Monsieur Bataille’, who appears alongside ‘Miss Struggle’ in the title of the work with the acephalous trunk, dubbed this struggle ‘base materialism’ before preferring the term ‘heterology’. Writing about the paintings in the Palaeolithic cave of Lascaux [4], Georges Bataille affirms the visceral link of ‘image acts’ [5] with eroticism, murder and the sacred. […]

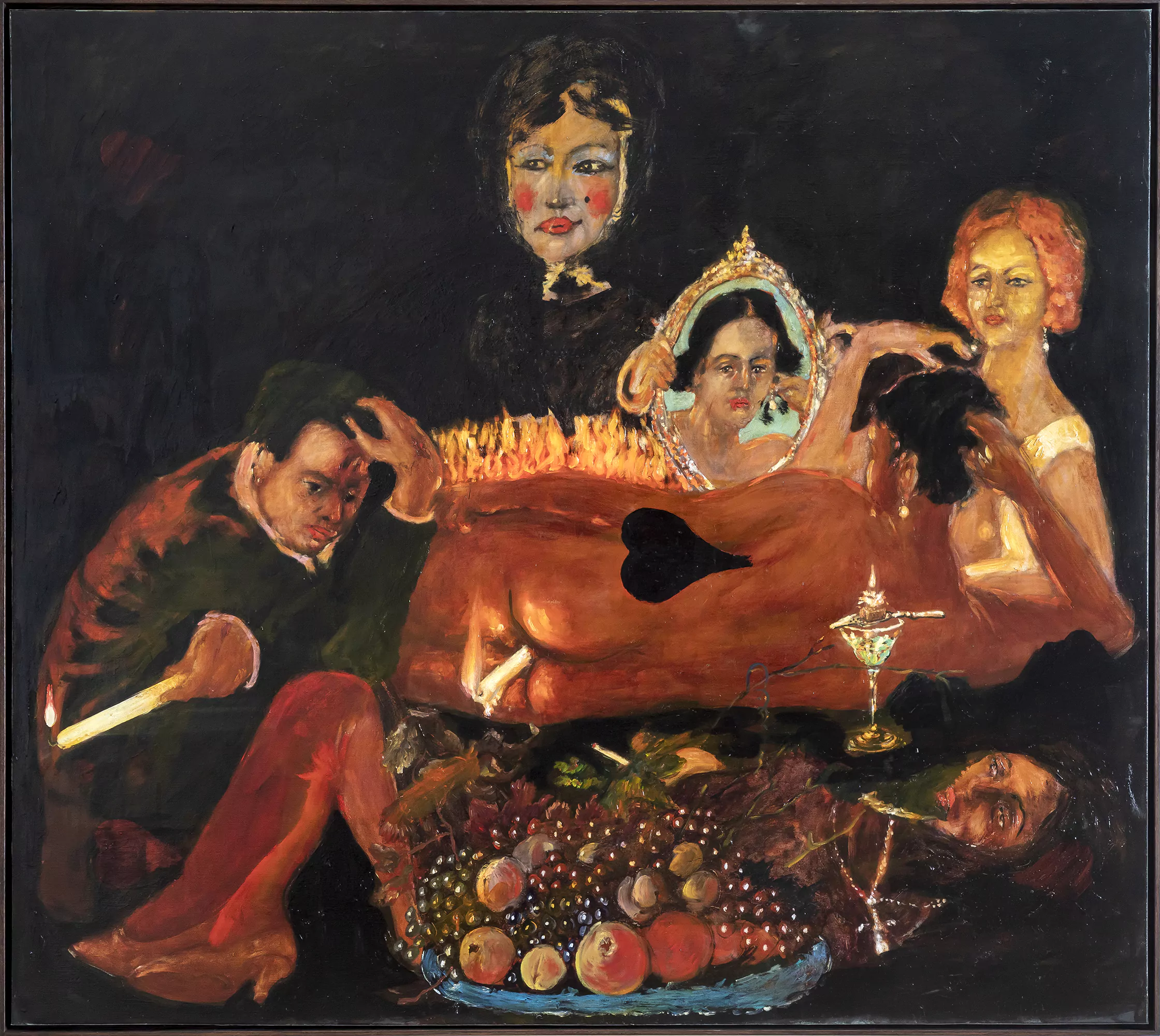

La réflexion sur le présent et les présents, 2021. Oil on canvas, 170 × 190 cm — 67 × 75 in.

DAY 3 / […]

I was wrong to think that Jan’s painting mimics the natural movement of material life by applying Newton’s laws to the things and bodies it de-figures. These streaks, which make a round, almost childlike, writing drool, extend the enterprise of desublimation to the painting itself. They highlight its surface quality, the flatness and material limitations of its support. […]

Altering what he has at hand, cutting down what history has elevated, is probably what Jan continues to do by creating a painting that brandishes its material condition, instructs nothing, tells nothing, and forsakes grand narratives and heroic gestures to highlight prosaic existences. […]

His cutting images give access to the the chasms

by superimposing layers,

by piling up surfaces.

DAY 5 / Yesterday, I was about to assert that Jan proceeds the way a surgeon uses his scalpel/a butcher uses his knife. Today, I changed my mind. His gesture does not slit matter, but rather adds matter to matter. His cutting images give access to the chasms by superimposing layers, by piling up surfaces. It took me some time to realise the obvious: that there is an elementary difference between the bodies Jan de-figures and the one we possess. Unlike the human body, which can only remain immobile for a limited time, these are frozen for an indeterminate time in a gesture, a scene, a system, a circuit of exchange. […] Gradually, I see them appear. The revenants. Motifs and objects that migrate from one canvas to another, past images that re-emerge once, twice and many more times to haunt the surfaces of the present. Unlike the unconscious ‘revenances’ that Warburg sought to highlight in his Mnemosyne Atlas, the revenants that Jan deploys are conscious resurgences. In other words, his paintings inhabit in full consciousness a territory already populated by a crowd of images, by peaks reached, chasms explored, already hierarchised by symbols. The present time of the image I contemplate is a montage of multiple and heterogeneous times. And Jan, who dismantles chronology, thus creates a very personal genealogy. […]

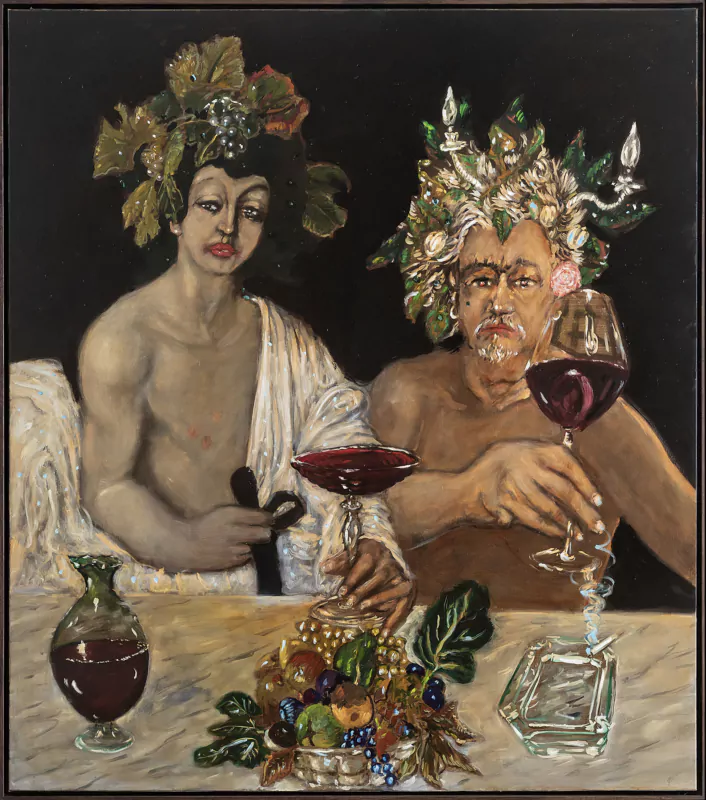

Le jeu des jumeaux d’antan. A shepherdess’ madness in a flying oyster bar, 2020. Oil on canvas, 190 × 170 cm – 75 × 67 in.

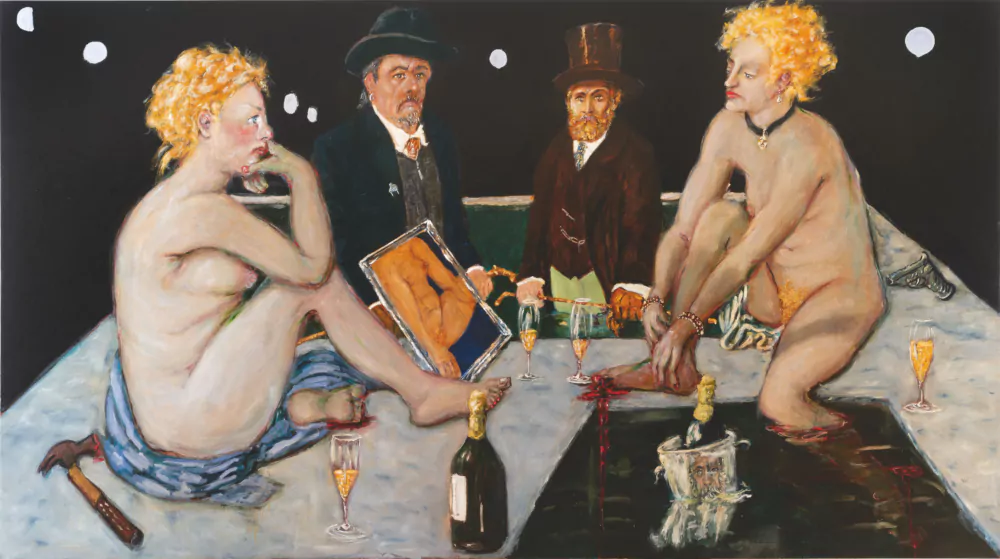

DAY 8 / From one ghost to another. I seem to be able to identify without difficulty the old image that resurfaces in L’Échange des bêtises with a new look. If commentators of the day are to be believed, Édouard Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe was greeted with horrified cries at its inaugural exhibition in 1863 at the Salon des refusés. […]

Manet profanes mythological and bucolic scenes represented by the older masters (Raphael, Titian, Giorgione) in order to subvert their well-behaved nudities and the pictorial conventions. Past, foreign or distant images return, never the same as themselves, never quite true to what they were; they return to a current place. Reinterpreting Manet’s reinterpretation, L’Échange des bêtises is a mise-en-abyme, a game of mirrors that attests that a ghost never comes alone. […] Jan brings everything to the foreground, in the sunlight: the water and the woman, whom he undresses in passing. His gesture readjusts the distances, reorganises the distribution of bodies and the circuit of gazes. It suppresses at the same time the elsewhere and the depth, establishes the reign of the here and the surface. Everything is there / nothing is there. […]

Times have changed since the offended cries of the Salon des refusés. The genitals made the veils drop; they emancipated themselves from the bedrooms, bathrooms, bucolic landscapes, painters’ studios, from those rare places where their nudity was acceptable. Now, they show themselves off, go out in the open without the need for excuses. The object of the scandal is no longer the genitals represented as exposed and naked in the variety of their states, of their actions, of their possible uses and in the variety of places. The ageless scandal consists of treating genitals (whatever they are) as we treat a face. […]

L’amélioration de l’inexistence, 2022. Oil on canvas, 170 × 150 cm – 67 × 59 in.

DAY 10 /[…]

The eel soup (Aalsuppe) is a traditional Hamburg dish prepared with leftovers and heterogeneous ingredients. This ‘all soup’ [6] did not originally contain eel. From one eel to another. […]

The eel-soup-without-eel is, so to speak, the price to pay for accessing the knots and complexity of existence. To grasp these knots, it is advisable to close one’s mouth, to open one’s eyes, and to look at the images that are the repository of them. Then it happens that, when looking at an image and its own knots, one sees the revenants: the crowd of past gestures which are given a new life by impregnating themselves with the current times. It is by looking at this knot of images, by seeking in the heterogeneous the spectacle of ‘a world that was taking on coherence’ [7], that Warburg found his head again after having lost it. On my whitewashed wall Curlieman, Baubo, Miss Struggle, Monsieur Bataille, Édouard, Aby, Madame Edwarda, Sainte-Victoire and all the others cohabitate in juxtaposition. I tell myself that, as far as Jan’s painting is concerned, the eel soup underlies the rejection of the aquarium. And that the way it raises and intensifies our base and heterogeneous lives makes it possible to grasp things with a blinding homogeneity.

L’échange des bêtises, 2021. Oil on canvas, 190 × 340 cm – 75 × 134 in.

—

Jan Van Imschoot, ‘The End is Never Near’

S.M.A.K., Ghent, Belgium,

until March 3rd, 2024.

SELEN ANSEN (b. 1975) is an art theorist and curator who lives and works in Istanbul. Holding a PhD in Theories and Practices of the Arts from Strasbourg March Bloch University, Ansen has taught in the fields of comparative literature, theory of the arts and aesthetics in various universities and superior art schools in France and Turkey. Since 2015, she has been Senior Curator at Arter, a non-profit institution for contemporary art based in Istanbul. Ansen has contributed to exhibition catalogues and artist monographs, and curated several exhibitions at an international level.

This text consists of selected excerpts from Selen Ansen’s essay “Eel Soup”, published in The End Is Never Near, a monograph coedited by S.M.A.K, Fonds Mercator and TEMPLON (2022).

[1] Monique Wittig, The Guérillères (London, 1971), p. 19.

[2] Georges Bataille, ‘Éponine’, Poèmes et nouvelles érotiques (Paris, 1999), p. 81 (quote translated from the French by Claire Cahm).

[3] The Romans associated Saturn with Cronos, the Greek god of Time, who devoured his own children one by one as they were born for fear of being dethroned by them.

[4] Lascaux; or, The Birth of Art by Georges Bataille was published the same year as his essay on Manet (1955).

[5] I use this with reference to the term ‘image acts’ coined by Horst Bredekamp. See Horst Bredekamp, Image Acts: A Systematic Approach to Visual Agency (Berlin/Boston, 2017).

[6] One might assume that this bizarre phrase stems from the phonetic proximity between the dialect terms aol suppe (all soup) and aalsuppe (eel soup).

[7] Julio Cortázar, Hopscotch (New York, 2016), p. 469.

Born in 1963 in Ghent, Jan Van Imschoot has been living and working in France since 2013. Jan Van Imschoot’s exploration of the possibilities offered by painting have resulted in a body of work that draws its power from highly critical and dramatic themes and contains references to countless artists, from Tintoret to Luc Tuymans, Goya to Matisse. Jan Van Imschoot places his figures, decors and narratives at History’s margins, using assembled perspectives, strong tones, bodies in motion and brushwork he describes as ‘anarcho-baroque’. His work delves into a number of recurring motifs: freedom, censorship and the violence of political and ideological systems.