Pop with pathos? George Segal’s phantoms

Essay

Art historian and curator Norman Kleeblatt illuminates the work of the most existentialist of Pop artists, George Segal, with a personal and retrospective vision.

Visitors to the Whitney Museum in late 2010 encountered George Segal’s monumental sculpture Walk, Don’t Walk, 1976 immediately upon exiting the beefy elevators of its Brutalist Breuer building. The arresting sculpture was the opening salvo for the exhibition “Singular Vision” and included three life-scale figures stopped at a pedestrian traffic signal. A found industrial traffic light set the stage; the figures were cast in Segal’s physically straightforward, yet complex plaster technique. The show, organized by Dana Miller and the then newly appointed curator Scott Rothkopf (now the Whitney’s director), offered curators the opportunity to closely examine the museum’s permanent collection and to select important, large-scale works that had not been on view for some time. As important, the range of the ten works shown did not readily conform with the clear stylistic categories and canonical assumptions still rigorously accepted at the time Segal grew to artistic maturity. Nine other similarly staged pieces complemented Segal’s installation and included an environment by Ed Kienholz, the heartbreaking death portrait of Felix Partz by AA Bronson, and an unusual boxing-rink installation by the painter/ draftsman Gary Simmons. Abstract work by minimalist Robert Grosvenor and a major post-minimal sculpture by Eva Hesse were also presented. Most of the art on view exploited weight and materiality, and most used or implied the figure. The strategy here was not to encourage the usual, smart connections and comparisons still common to standard curatorial practice. By creating discrete spaces to display each of the featured projects, the curators instead invited viewers to slow down, concentrate, and interact intimately with each work, one at a time.

Segal’s mature sculpture emerged as Pop Art rose to its ascendancy; his environments initially sequestered along with the then current, cool, detached, media-obsessed movement. From the start, Segal’s signature style of casting and the psychological ambiguity and complexity of his figures left critics stammering. Typing and placing Segal’s art into the matrix of art produced in New York during the 1960s and 1970s was not easy. To wit: in 1963, both Segal and Warhol were commissioned to create portraits of the protean collectors of new art-Ethel and Robert Scull. Warhol’s iconic Ethel Scull, thirty-six times, was completed that same year. Segal’s double portrait appeared two years later. With such prescient commissions from the ultimate insiders, the Sculls, it was natural to position Segal as a leader in the same circle that in addition to Andy Warhol, included Roy Lichtenstein, and Claes Oldenburg among others. In due course, Robert Scull became dubbed the “pop of Pop,” and hoped to be considered “…[L]ike the guy who sponsored Giotto’s frescoes.” It follows that one might fairly consider both Warhol and Segal the court portraitists of the movement. Top collectors of Abstract Expressionist art and of Pop Art, the Sculls also financed Richard Bellamy’s influential Green Gallery where Segal was part of its stable.[1]

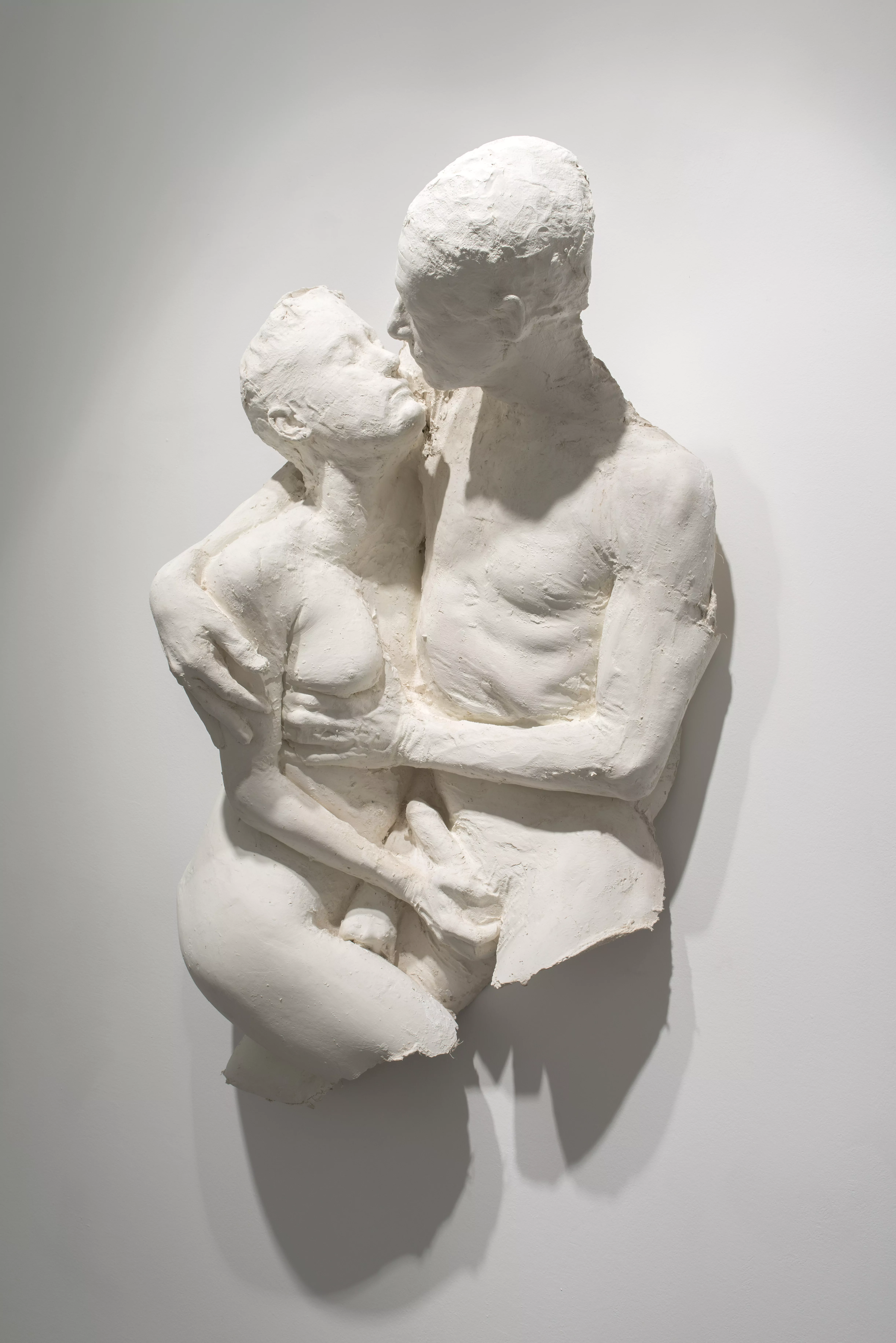

Miles & Monique, c.1980. Plaster and paint, 122 × 61 × 38 cm – 48 × 24 × 15 in.

The discussion of where Segal’s art could be located within the contemporary scene is much debated in the literature on the artist, especially in his early career. In many ways positioning Segal remains as difficult as was the case for his forbear and major influence, Lithuanian-born Parisian painter Chaim Soutine. George and I spoke extensively of his veneration for Soutine and Soutine’s important influence early in Segal’s career. Soutine’s 1950 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art would certainly have been important for the youthful Segal who was just beginning to earn his creds in art and art history. I drew on input from Segal for the programming around the 1998 Soutine monograph I co-curated at the Jewish Museum, New York. For like Segal, the master of the École de Paris is not-easily categorized; his expressionist style is a contradiction to much of the inter-war School of Paris painting [2]. Like Soutine’s un-Parisian interwar expressionism—more Germanic than French-one commentator, Joan Pachner, observed that the pathos of Segal’s remote, often desolate figures does not fit with what she called the “upbeat emotional pathos” of Pop [3]. Was the paradox of Pachner’s phrase intentional? Martin Friedman, the risk-taking director of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, called Segal’s work “an anomaly… its descriptive, introspective character out of phase… with the ironic commentary of his [Pop] contemporaries….” [4]

Simply put, Segal himself felt that his work combined both formal and expressive elements of the preceding Abstract Expressionist movement, joining them with aspects of the Pop phenomenon. His personal reflections offer a more complex picture of what he was after within the sensibilities of what were in fact the artistically diverse, often divisive, and complicated 1960s—more so than generally acknowledged at the time. In 1967, the South Brunswick, New Jersey sculptor, Segal recalled that the decade was “characterized by a unique openness of attitude, a willingness to use unfamiliar materials, forms, and unorthodox stances in the work produced, an unwillingness to accept standard value judgments, a tendency to probe, act, live, and work with final judgement suspended, an appreciation of the mystery, unknowability, ambiguity of the simplest things.” [5]

The multi-dimensional insights of Segal’s observations clearly reflect a highly nuanced understanding of that decade including at very least the Happenings pioneered by his close friend Allan Kaprow and the transatlantic Fluxus movement. The critical attempts to find a secure— yes, even contradictory—place for Segal within a usual art historical box however has led to expanded perspectives on the sculptor’s singular vision. Major art historians and curators took their turn offering interpretations about Segal’s art. One of the most unusual of such discussions is a filmed visit to Segal’s studio by the legendary, broad-ranging art historian Meyer Schapiro. Coincidentally Schapiro, like Segal, was also an energetic enthusiast for the work of Chaim Soutine, discussing Soutine’s works in his classes and ultimately prompting the Museum of Modern Art’s first US retrospective on the artist [6]. The Segal/ Schapiro interview was produced and directed by Michael Blackwood, the noted filmmaker who created documentaries of numerous major artists of the period, including among others Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, Vija Celmins, and Philip Guston. The visit of Schapiro to Segal’s modified chicken coop/studio in South Brunswick offers intimate glimpses of the mutual interests that grounded the relationship between sculptor and art historian as well as their common humanist sensibilities. In the film Schapiro teases out impressive aspects of Segal’s sculpture and thinking. Segal comments smartly on the contradictory nature of the Greek sculptural ideal with what he calls an “abominable travesty of [modern] beauty”- the department store mannequin. Similarly, Segal critiques how the emotive abstraction of the preceding generation of the Abstract Expressionists “ignore[s] flesh and blood.” Segal regales Schapiro with his long evening bar hopping with Barnett Newman in which a discussion ensues about Newman’s iconic Abraham, 1949, one of the Abstract Expressionist’s early zips. Segal challenges the epic Abstract Expressionist, claiming that Newman’s highly controlled abstraction, which the older artist claimed to be a personal reckoning with both his father and the biblical patriarch, was becoming so “pure” it was divorced from flesh [7].

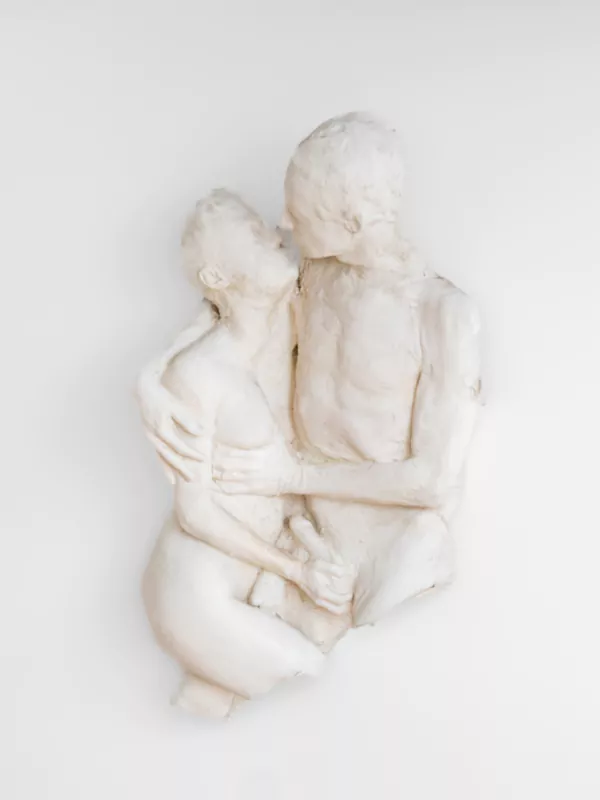

Body Fragment #4, 1980. Plaster and paint, 76 × 51 × 13 cm – 30 × 20 × 5 in.

On the other hand, Schapiro reaches back into earlier modernism, comparing Segal’s interest in the commonplace in general and the worker specifically with figures in certain paintings by the Impressionist Gustave Caillebotte. And, you guessed it, the figures in Soutine’s paintings are also mentioned. Around 1979, when the film was made, Segal had already begun adding color to some of his figures for almost a decade. Schapiro talks about the differences between colors from nature, e.g. green and ochre, and the multiple meanings of more symbolic colors such as blue. In his broad learned approach to art, life, and literature, the famed art historian and thinker calls on Keats and Goethe. Smartly Schapiro remarked on the paradoxical artifice of Segal’s plasters set into scenarios with “real” scavenged, discarded objects from everyday life. Ultimately the famed art historian found mystery and strangeness in what he calls Segal’s environments and considered the sculptor’s figures a “phantom[s] in three dimensions.” [8]

Other art historians also probed deeply — symbolically, metaphorically, and historically — into the meanings and effects of Segal’s art. For one, Martin Friedman commented on the artist’s “effort to symbolize the fusion of matter and spirit” and how this can result in “a cabbalistic experience.” [9] Classical art is frequently mentioned in relation to Segal’s sculpture, but of course there are also biblical references and resonances. Figures like Charon and Venus, Abraham and Noah are comparatively noted throughout the literature. A wide range of art historical references spans millennia: Old Kingdom Egyptian statuary, Giotto—a favorite of Segal, Donatello, as well as Degas, Soutine, and naturally Hopper. The color added to his later figures also has been discussed as response to Ellsworth Kelly’s calculated abstractions and Barnett Newman’s color fields. Cited as well are Segal’s obvious influences (as well as radical contrast with) the sculptors John de Andrea and Duane Hanson. Important artists of prior generations also weighed in: Marcel Duchamp carefully juxtaposing Segal’s deployment of everyday objects to his own early 20th century invention of Dada. Duchamp claimed that “with Segal it is not a matter of the found object, it’s the chosen object.” [10] Interesting that there are relatively few literary, theatrical, or filmic references in the writing on Segal. Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream is mentioned in reference to Segal’s unusual—somewhat surreal— The Costume Party, 1972 as well as the chance mention of the existentialist writer Samuel Beckett. This is true despite Segal’s frequent discussions of the influence of Hollywood on him and his personal struggle with commercial cinema’s predictability and conceits. Segal’s figures relate to the characters in the plays of Sam Shepard, who though nearly a generation younger than Segal was already becoming active in the early 1960s. Described as “ghosts,” [11] “mummies,” [12] “golems,” [13] and “phantoms,” [14] one might consider Segal’s figural actors’ “hermetic insularity” [15] sharing the desolation of Shepherd’s characters but lacking the playwright’s utter desperation. Early interpretation of the South Brunswick sculptor coincided with the idea of “theatricality” as a dirty word for art. Nevertheless, what are Segal’s stage sets if not theatrical, despite the subtle, understated, and ambiguous nature of their emotive substance. Such contemporaneous literary, yes theatrical, references would offer new insights into George Segal’s sculpture as well as the nature of the US psyche at the time.

—

George Segal, ‘Nocturnal Fragments’

Templon New York, until October 28, 2023.

NORMAN KLEEBLATT is an independent curator, critic, and the current president of the United States chapter of International Association of Art Critics. He is the former chief curator at The Jewish Museum, New York. Kleeblatt has organized many major exhibitions including the award-winning “Action/Abstraction: Pollock, De Kooning, and American Art, 1940-1976” (2008) and “From the Margins: Lee Krasner and Norman Lewis, 1945-1952” (2014). Kleeblatt contributes essays to museum and gallery catalogues as well as publications including ARTnews, Artforum, Art Journal, and Art in America, Hyperallergic, and Brooklyn Rail.

[1] Judith E. Stein, The Eye of the Sixties; Richard Bellamy and the Transformation of Modern Art, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016: 20-210, 215, 247. Melissa Rachleff Burtt, Inventing Downtown: Artist-Run Galleries in New York City, 1952-1965, 2017 ex.cat. pp.224-225.

[2] See Kenneth E. Silver, “Where Soutine Belongs: His Art and Critical Reception in Paris Between the Wars” in Norman L. Kleeblatt and Kenneth E. Silver (Eds.), An Expressionist in Paris: The Paintings of Chaim Soutine, Munich: Prestel, 1998, p. 19.

[3] Joan Pachner, “George Segal” in George Segal, Carroll Janis, and Joan Pachner, George Segal: Bronze, Exh. Cat., New York: Mitchell-Innis Nash, p. 17.

[4] Martin Friedman, George Segal: Proletarian Mythmaker, Exh. Cat., 1978, The Walker Art Center. p.9.

[5] Barbara Rose and Irving Sandler, “Sensibilities of the Sixties,” Art in America, Vol. 55, No. 1, January-February, 1967. p. 55.

[6] Monroe Wheeler, Soutine, Exh. Cat., New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1950. Meyer Schapiro’s advocacy of a Soutine retrospective in the US, more specifically in New York, was longstanding, starting shortly after Soutine’s death in 1943 and the end of WWII.

[7] Michael Blackwood Productions, “The Artist’s Studio: Meyer Schapiro Visits George Segal”, 2018 [1979]. Retrieved September 2, 2023, from: https://vimeo.com/ondemand/schapirosegal. In a 1986 essay for a George Segal catalogue at the Sidney Janis gallery, noted art historian Robert Rosenblum uses similar descriptions to Schapiro’s 1979 comments. Here Rosenblum talks about “discrepancies between artifice and reality.” Robert Rosenblum, George Segal, Exh. Cat., New York: Sidney Janis Gallery, 1986.<

[8] Ibid.

[9] Martin Friedman, op.cit. p. 23.

[10] Jan Van Der Marck, George Segal, New York: Abrams, 1975. p.26.

[11] Sam Hunter, George Segal, New York: Rizzoli, 1989, p.6.

[12] Allan Kaprow, “Segal’s vital mummies,” Art News, February 1964, pp. 30-34.

[13] Sam Hunter, op. cit., p. 6.

[14] Meyer Schapiro in Michael Blackwood Productions, op. cit.

[15] Sidra Stich, Made in U.S.A.: an Americanization in modern art, the ’50s & ’60s, Exh. Cat., Berkeley: University Art Museum, University of California, Berkeley : University of California Press, 1987., p.72.